A few years ago, I posted my ‘New Year’s Message’. Well, if it’s good enough for the sodding Pope, the then Queen (she croaked last year), our Presidents, Prime Ministers, CEOs and the chap in charge of the car pool at the depot, it’s good enough for me. So I shall do it again, but I shan’t give you the usual blather (well, try not to) as there will be enough of that for the next 365 days.

Yes, ‘things will be tough’, but then when weren’t they? And let’s face it, not only will they be far tougher for some than others but, crucially, one man’s ‘tough’ is another man’s ‘well, aren’t some the lucky ones?’

Years ago when lived in London, I went to the theatre once or twice, and at Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square I saw Six Degrees Of Separation, an entertaining enough play. I mention it because I seemed to remember one line which sums up well the discrepancy in our many different lives.

But as it turns out, I don’t. I’ve just looked up the script of the play and can’t find the line or variations of it anywhere. But it’s still a good line, and my memory of it runs like this: a character complains of ‘living on the breadline’, to which another character replies

We’re all on the breadline but start from a different base.Quite.

Just as for some ‘a tragedy’ is leaving the house without their smartphone - horror! - or possibly even worse, discovering just as they are leaving that they have forgotten to charge it overnight!, for others tragedy is rather closer to what might be described as ‘true tragedy’.

For many in Ukraine, their lives are in some ways tragic: they were attacked without cause by Russia and the onslaught continues, and there seems no end to it. What makes it all the worse is that if - if - Putin’s spurious ‘justification’ - that he is ‘protecting’ Russia and that, anyway, Ukraine is an ‘artificial state’ and, in fact, part of Russia - held any water, he is still on a hiding to nothing.

At present his ‘military operation’ has been so piss-poor that tens of thousands of Russian troops have been killed, he has not gained any territory and what support he might have had from men and women living in the Donetsk area will vanishing as they see their homes and communities reduced to rubble and many have been murdered.

Even if by some fluke his troops do manage to ‘conquer’ Ukraine, how on earth does Putin think Russia can hold on to it? That he knows he is on to a loser is obvious from the hints he’s making about ‘peace’ talks. He is trying to spin the situation into it seeming that the Ukrainians are unwilling to negotiate and a barrier to a ceasefire and ‘peace’. Well, not quite, Vlad laddie.

Definite demands from Ukraine, the sine qua non of all negotiation, will be that all Russian troops are withdrawn from all Ukrainian territory and that Russia makes full reparation for the damage it has caused and - though quite who do you make ‘reparation’ for human life? - for the deaths it has been responsible for.

There will certainly be pressure on Ukraine and her president Volodymyr Zelenskyy to ‘compromise’ to ensure the war ends as soon as possible, but it is almost impossible to see how Ukraine might ‘compromise’: the demands outlined above are surely the very, very least Russia must comply with.

But this is politics: the West has been surprisingly supportive of Ukraine and after Putin shut off supplies of the gas Russia supplies Europe with, energy bills have shot up. So far there has been little dissent, but there is some dissent.

Why, some right-wing politicos in Europe and, crucially, the US are asking, are we making this sacrifice? Well, actually the answer is obvious but, ironically, cannot be articulated: we are doing our very best to limit Russia’s power and influence and given the thuggish nature of its leaders in the past, both immediate and distant, that seems like a sensible objective.

The problem is we can’t spell out that objective because that would play right into Putin’s hands: he contends that the US and the West are ‘out to get Russia, to destroy the country’.

That his contention doesn’t hold water for a second is neither here nor there: all he need to is convince the Russian people those are the West’s intentions and they will gather behind him to support him. Perception is all.

‘His contention doesn’t hold water?’ I hear you asking. How do you work that out? Well, it is remarkably straightforward. The age of empires has long passed.

And even in that age the objective was not to hold land and ‘be boss’ just to hold land and ‘be boss’: the whole point was to ensure access to the resources of those lands - cheaply - and, latterly, to turn them into ‘markets’ for goods produced by the relevant imperial power.

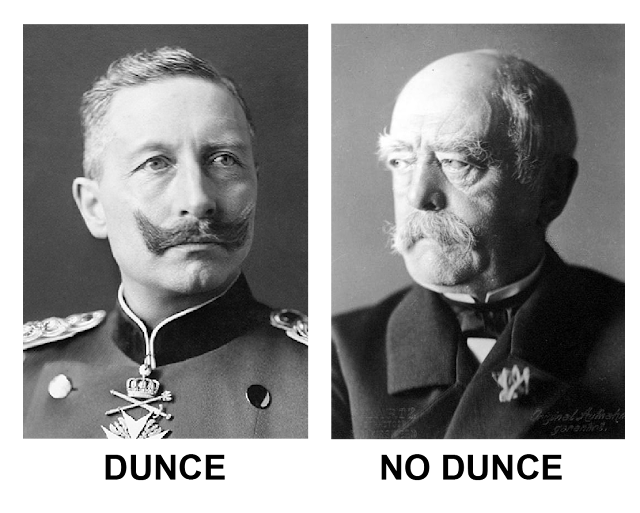

Certainly, there were some imperialists who were dazzled by the ‘prestige’ of ‘being the boss’, but such folk were - in the eyes of business and commerce - simpletons. A comparatively recent example would be Germany Kaiser Wilhelm II: arguably he had both a chip on his shoulder and wasn’t very bright.

He was certainly thought by some to have a certain ‘quick’ intelligence but in may book he is a prime example of how ‘intelligent’ people are often quite stupid.

For many in Ukraine, their lives are in some ways tragic: they were attacked without cause by Russia and the onslaught continues, and there seems no end to it. What makes it all the worse is that if - if - Putin’s spurious ‘justification’ - that he is ‘protecting’ Russia and that, anyway, Ukraine is an ‘artificial state’ and, in fact, part of Russia - held any water, he is still on a hiding to nothing.

At present his ‘military operation’ has been so piss-poor that tens of thousands of Russian troops have been killed, he has not gained any territory and what support he might have had from men and women living in the Donetsk area will vanishing as they see their homes and communities reduced to rubble and many have been murdered.

Even if by some fluke his troops do manage to ‘conquer’ Ukraine, how on earth does Putin think Russia can hold on to it? That he knows he is on to a loser is obvious from the hints he’s making about ‘peace’ talks. He is trying to spin the situation into it seeming that the Ukrainians are unwilling to negotiate and a barrier to a ceasefire and ‘peace’. Well, not quite, Vlad laddie.

Definite demands from Ukraine, the sine qua non of all negotiation, will be that all Russian troops are withdrawn from all Ukrainian territory and that Russia makes full reparation for the damage it has caused and - though quite who do you make ‘reparation’ for human life? - for the deaths it has been responsible for.

There will certainly be pressure on Ukraine and her president Volodymyr Zelenskyy to ‘compromise’ to ensure the war ends as soon as possible, but it is almost impossible to see how Ukraine might ‘compromise’: the demands outlined above are surely the very, very least Russia must comply with.

But this is politics: the West has been surprisingly supportive of Ukraine and after Putin shut off supplies of the gas Russia supplies Europe with, energy bills have shot up. So far there has been little dissent, but there is some dissent.

Why, some right-wing politicos in Europe and, crucially, the US are asking, are we making this sacrifice? Well, actually the answer is obvious but, ironically, cannot be articulated: we are doing our very best to limit Russia’s power and influence and given the thuggish nature of its leaders in the past, both immediate and distant, that seems like a sensible objective.

The problem is we can’t spell out that objective because that would play right into Putin’s hands: he contends that the US and the West are ‘out to get Russia, to destroy the country’.

That his contention doesn’t hold water for a second is neither here nor there: all he need to is convince the Russian people those are the West’s intentions and they will gather behind him to support him. Perception is all.

‘His contention doesn’t hold water?’ I hear you asking. How do you work that out? Well, it is remarkably straightforward. The age of empires has long passed.

And even in that age the objective was not to hold land and ‘be boss’ just to hold land and ‘be boss’: the whole point was to ensure access to the resources of those lands - cheaply - and, latterly, to turn them into ‘markets’ for goods produced by the relevant imperial power.

Certainly, there were some imperialists who were dazzled by the ‘prestige’ of ‘being the boss’, but such folk were - in the eyes of business and commerce - simpletons. A comparatively recent example would be Germany Kaiser Wilhelm II: arguably he had both a chip on his shoulder and wasn’t very bright.

He was certainly thought by some to have a certain ‘quick’ intelligence but in may book he is a prime example of how ‘intelligent’ people are often quite stupid.

When evaluating someone’s ‘intelligence’ - at the end of the day a concept so vague as to mean little - it might help if we took a far broader view of their personality and behaviour and the results of their actions. Seen that way Wilhelm II was rather thick.

Envious of the British empire ‘ruled’ by his grandmother Queen Victoria and then his cousin King Edward VII, he believed Germany should also have an empire and set about trying to acquire one in East Africa and South-West Africa. He didn’t get very far.

One of Germany’s main strengths was its deeply cynical but very effective chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Yet Bismarck was also a pragmatist: he certainly wanted Germany to thrive and sit at the top table but only if the price was right. He was against starting wars simply for the sake of starting wars and gaining ‘prestige’. Wilhelm II was.

Bismarck lasted for 12 years after Wilhelm II’s accession as Kaiser, but was finally forced to resign. Arguably, that’s when - in 1890 - the process leading to World War I (‘The Great War’) which began 24 years later began. Bismarck would not have let it happen (though by then he would have been 99 and most probably would long have been dead).

Humankind has been said to be distinguished not by its ability to ‘be rational’ but by its tendency often to ‘behave irrationally’. Putin has certainly behaved irrationally by invading Ukraine (and is now paying the price). And his contention that the West is out to destroy Russia - which I’m not too sure he even believes himself - is also irrational.

The US and the West want stability and that is what the people of its nations want it to provide. I would bet my bottom rouble that is also what the vast majority of Russians want: a quiet, peaceful life.

Envious of the British empire ‘ruled’ by his grandmother Queen Victoria and then his cousin King Edward VII, he believed Germany should also have an empire and set about trying to acquire one in East Africa and South-West Africa. He didn’t get very far.

One of Germany’s main strengths was its deeply cynical but very effective chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Yet Bismarck was also a pragmatist: he certainly wanted Germany to thrive and sit at the top table but only if the price was right. He was against starting wars simply for the sake of starting wars and gaining ‘prestige’. Wilhelm II was.

Bismarck lasted for 12 years after Wilhelm II’s accession as Kaiser, but was finally forced to resign. Arguably, that’s when - in 1890 - the process leading to World War I (‘The Great War’) which began 24 years later began. Bismarck would not have let it happen (though by then he would have been 99 and most probably would long have been dead).

. . .

Humankind has been said to be distinguished not by its ability to ‘be rational’ but by its tendency often to ‘behave irrationally’. Putin has certainly behaved irrationally by invading Ukraine (and is now paying the price). And his contention that the West is out to destroy Russia - which I’m not too sure he even believes himself - is also irrational.

The US and the West want stability and that is what the people of its nations want it to provide. I would bet my bottom rouble that is also what the vast majority of Russians want: a quiet, peaceful life.

The US and the West are not interested in acquiring territory. All they want to acquire is more markets and the various missteps of history have shown us that in the 21st century peace and stability ensure that markets grow. Wars don't (except for the Daddy Warbucks of all nationalities).

Ideally we would want a Russia that is prosperous enough to buy all the shite we want to sell it. And frankly who cares whether Russia is a ‘liberal democracy’ with ‘free and fair elections’ or run by a corrupt thug? However, what business does care about is ‘the rule of law’, but this is purely of pragmatic reasons not ethical ones.

‘The rule of law’ and a decent justice system (though there is more to the rule of law than just its justice system) will make it safer to invest in Russia and do business there. And if there is contractual disagreement, a civil court system business can trust is worth its weight in gold. And Russia most certainly does not have that.

But what Russia did have, however flawed it seems in the eyes of the West (which, er, is certainly not perfect) is preferable to the situation there is now. Frankly, Putin doesn’t need to fear the US and the West are out to ‘destroy Russia’. He is doing a fine job all on his own.

As for his gripe that Nato is expanding, well by invading Ukraine and tacitly threatening its other neighbouring countries, the bright little spark has ensured exactly that is now happening with several previously neutral countries knocking on the door and asking to be let in. Clever Putin, once suspected of being ‘a master strategist’, is another example how ‘intelligent’ people can often be remarkably stupid. The first Dunce’s Cap to you, Mr Putin.

Another candidate for the Dunce’s Cap is one Xi Jinping. And he, too, is proving he has, to the surprise of many, feet of clay. Perhaps he first piece of stupidity was to get himself to be declared - more or less - ‘boss of China for life’ last October.

I have just spent a few minutes trying to establish what his official ‘job’ is now, but didn’t get far. Whether he is ‘boss of China’ by being head honcho of the Chinese Communist Party, as China’s president or chairman of the Central Military Commission is neither here nor there: Xi now calls the shots.

And China is not like, say, Britain where a ‘vote of no confidence’ might trigger the Prime Minister’s resignation. More so than before - and it might be argued that in the decades leading to Xi’s accession China has seen ‘a more liberal’ totalitarian state - Xi rules by fear. But 2023 might see him come unstuck, though I for one am not keeping my fingers crossed given the disruption that might cause.

Like pretty much everywhere else, if the people are content they are apt to give you no trouble. The students and idealists and revolutionaries might bang on about principles and free elections and I don’t know what else, but all other things being equal of folk have a reasonably trouble-free life - even if their neighbours don’t - they are apt not to rock the boat.

Xi’s stupidity consists of seemingly to ignore that simple truth. Whether or not covid originated in a laboratory in Wuhan, China, or not is also neither here nor there. Xi’s immediate response was for ‘zero-covid’ - a total lockdown.

What is crucial is that it wasn’t, for a while, the discontent of the locked-down people that was damaging but the impact it had on the economy. Some factories were either forced to shut or their workers were locked in at the factory and both worked and lived there.

The impact on the economy gradually became apparent, and then so did the people’s discontent so that a few weeks ago there were street protests. There are, it seems, quite a few street protests in Chinese and we in the West don’t much hear of them.

They were almost all a bout local issues and thus of little impact nationwide. But these protests were different: there were calls for Xi to go, and such public lèse-majesté was new. More than that, despite the stranglehold on the internet in China word got around fast.

What did stupid Xi do? Overnight he abolished all lockdown restrictions - and covid is now spreading like wildfire. The danger to the rest of the world, which broadly has conquered the pandemic, is that covid, and possibly new strains, will go global and we shall be back to square one. Yippee!

Stupid Xi is also demonstrating quite how inept - and irrational - he is by ratcheting up the tensions with Taiwan. This is a throwback to the ‘age of empires’. China has long insisted that Taiwan is not an independent state but a rogue province. Fair enough, and who cares, as long was the situation remains peaceful.

Xi, though, has a bee in his bonnet - think silly old Kaiser Wilhelm II - that Taiwan must be re-incorporated into China. And he has indicated that he intends doing so sooner rather than later. Why? Well, ask Xi. Who knows?

This is bad news all round, not just for that neck of the Far Eastern world (obviously seen from a narrow Western perspective - for China Europe is the Far Western world) but for all of us. If we think covid has damaged the global economy, consider what war between China and Taiwan will mean. And it might - or might not - involve the US.

Welcome to 2023 and what might be called the Age of Dunces.

Ideally we would want a Russia that is prosperous enough to buy all the shite we want to sell it. And frankly who cares whether Russia is a ‘liberal democracy’ with ‘free and fair elections’ or run by a corrupt thug? However, what business does care about is ‘the rule of law’, but this is purely of pragmatic reasons not ethical ones.

‘The rule of law’ and a decent justice system (though there is more to the rule of law than just its justice system) will make it safer to invest in Russia and do business there. And if there is contractual disagreement, a civil court system business can trust is worth its weight in gold. And Russia most certainly does not have that.

But what Russia did have, however flawed it seems in the eyes of the West (which, er, is certainly not perfect) is preferable to the situation there is now. Frankly, Putin doesn’t need to fear the US and the West are out to ‘destroy Russia’. He is doing a fine job all on his own.

As for his gripe that Nato is expanding, well by invading Ukraine and tacitly threatening its other neighbouring countries, the bright little spark has ensured exactly that is now happening with several previously neutral countries knocking on the door and asking to be let in. Clever Putin, once suspected of being ‘a master strategist’, is another example how ‘intelligent’ people can often be remarkably stupid. The first Dunce’s Cap to you, Mr Putin.

. . .

Another candidate for the Dunce’s Cap is one Xi Jinping. And he, too, is proving he has, to the surprise of many, feet of clay. Perhaps he first piece of stupidity was to get himself to be declared - more or less - ‘boss of China for life’ last October.

I have just spent a few minutes trying to establish what his official ‘job’ is now, but didn’t get far. Whether he is ‘boss of China’ by being head honcho of the Chinese Communist Party, as China’s president or chairman of the Central Military Commission is neither here nor there: Xi now calls the shots.

And China is not like, say, Britain where a ‘vote of no confidence’ might trigger the Prime Minister’s resignation. More so than before - and it might be argued that in the decades leading to Xi’s accession China has seen ‘a more liberal’ totalitarian state - Xi rules by fear. But 2023 might see him come unstuck, though I for one am not keeping my fingers crossed given the disruption that might cause.

Like pretty much everywhere else, if the people are content they are apt to give you no trouble. The students and idealists and revolutionaries might bang on about principles and free elections and I don’t know what else, but all other things being equal of folk have a reasonably trouble-free life - even if their neighbours don’t - they are apt not to rock the boat.

Xi’s stupidity consists of seemingly to ignore that simple truth. Whether or not covid originated in a laboratory in Wuhan, China, or not is also neither here nor there. Xi’s immediate response was for ‘zero-covid’ - a total lockdown.

What is crucial is that it wasn’t, for a while, the discontent of the locked-down people that was damaging but the impact it had on the economy. Some factories were either forced to shut or their workers were locked in at the factory and both worked and lived there.

The impact on the economy gradually became apparent, and then so did the people’s discontent so that a few weeks ago there were street protests. There are, it seems, quite a few street protests in Chinese and we in the West don’t much hear of them.

They were almost all a bout local issues and thus of little impact nationwide. But these protests were different: there were calls for Xi to go, and such public lèse-majesté was new. More than that, despite the stranglehold on the internet in China word got around fast.

What did stupid Xi do? Overnight he abolished all lockdown restrictions - and covid is now spreading like wildfire. The danger to the rest of the world, which broadly has conquered the pandemic, is that covid, and possibly new strains, will go global and we shall be back to square one. Yippee!

Stupid Xi is also demonstrating quite how inept - and irrational - he is by ratcheting up the tensions with Taiwan. This is a throwback to the ‘age of empires’. China has long insisted that Taiwan is not an independent state but a rogue province. Fair enough, and who cares, as long was the situation remains peaceful.

Xi, though, has a bee in his bonnet - think silly old Kaiser Wilhelm II - that Taiwan must be re-incorporated into China. And he has indicated that he intends doing so sooner rather than later. Why? Well, ask Xi. Who knows?

This is bad news all round, not just for that neck of the Far Eastern world (obviously seen from a narrow Western perspective - for China Europe is the Far Western world) but for all of us. If we think covid has damaged the global economy, consider what war between China and Taiwan will mean. And it might - or might not - involve the US.

Welcome to 2023 and what might be called the Age of Dunces.