Sitting down to review Josephine Tey’s The Daughter Of Time puts me in a bit of a quandary: it has – apparently – been voted the No 1 Crime Novel of All Time by the UK Crime Writers Association. In the US the Mystery Writers of America voted it the fourth best ‘mystery novel of all time’.

But, frankly, those opening it and hoping to settle in for a rattling good murder mystery might well find themselves short-changed: it is not typical of its kind and that is putting it mildly.

It was published in 1951 and features Alan Grant, one of Tey’s recurring main characters, a Scotland Yard detective who is laid up in hospital with a broken leg and is bored out of his mind. Friends have dropped off a number of ‘fashionable’ books for him to read but isn’t interested in any of them.

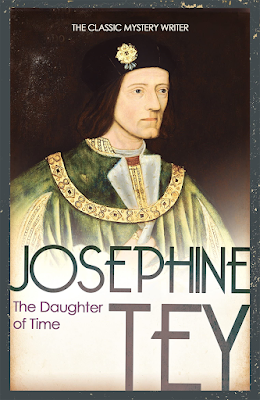

There follows a sequence of events – we never move out of Grant’s hospital room at any point – starting with a visitor bringing him pictures and portraits of various people: Grant has asked her to bring some in as he rather fancies himself as a sure judge of character from a man or woman’s features. Finally, he comes across a portrait – there really is only one extant – of Richard III, the evil king who reputedly had his two young nephews murdered so he could usurp the throne as king of England.

Grant considers Richard’s face, decides it is that of an essentially kindly man and finds it impossible to accept that he had – as was and still is repeatedly claimed over the centuries – murdered (or had murdered on his behalf) two innocent young princes in the Tower of London.

Richard had been popular, loved even, respected, had a strong moral sense of duty and had no compunction about standing up for the rights of the least of those in his charge against overbearing nobility (which did not make him popular with some of the nobility).

From everything that was reported about the man, it would have been wholly out of character and none of it bears any resemblance to the ‘evil hunchback’ of Shakespeare’s play or of Sir Thomas More’s biography.

The rest of the novel is taken up by Grant sifting through all the evidence put forward to ‘convict’ Richard of being guilty of the evil deed and concluding that it was a stitch-up perpetuated by Henry Tudor, the man who beat him at the Battle of Bosworth who went on to become Henry VII.

Even before reading Tey’s book, I had taken an interest in and read up on the matter and had long decided that Richard was innocent and that Henry Tudor was almost certainly responsible for the two princes deaths.

But as this is a review of Tey’s novel rather than a discussion of whether Richard was a monster or not, it would be redundant here to marshal all the evidence considered by Grant. The only thing necessary to mention here is that in all his ‘sleuthing’ Grant is assisted by a young American visiting London – an oddly irrelevant detail – who does all the legwork for him, looking up documents in the British Museum and elsewhere.

If you are also interested in whether or not Richard was stitched-up, the evidence laid in Tey’s novel will interest you. If you are looking to settle down to a rattling good crime mystery, I suspect some, if not many, will be disappointed.

For one thing there is no mystery: the novel consists solely of Grant and his young American friend discussing the evidence, and is made up almost entirely of dialogue and the discussions between Grant and Carradine and – a black mark for any writer – it is often not at all clear who is speaking.

Tey includes various minor characters but they are virtual cardboard cutouts. The best ‘crime mystery story of all time’? Not from where I sit.

As a concise summary of the evidence that Richard III was – almost certainly – innocent and that Henry Tudor was trying to justify his own usurpation, it succeeds. If you are looking from a gripping crime novel, move on. This is not it.

No comments:

Post a Comment