Sunday 29 March 2020

Saturday 28 March 2020

This ’n that — Ruskies, Commies, good guys, bad guys, morons like Trump, the Cold War, Jim Crow, lynching blacks, Howard Zinn, Billie Holiday — it’s strange what occurs to you sometimes of an hour

When I was a kid growing up in the 1950s - ten years old in 1960 - ‘America’, by which we meant the US, was in an odd sort of way a kind of Nirvana. It was, we were led to believe, where everything worked and worked well, everything was efficient, everyone was well off, everyone was attractive, life was glamorous. America was slick, cool, and, for us in Britain at least, but also in post-World War II Europe and especially then West Germany, somewhere to be envied. It is pertinent that, as I say, when we spoke of ‘America’ we meant, and often still do, the United States. Bugger Canada, Mexico, Central America and the several huge nations to the south, ‘America’ was the United States.

At least two things were at play here and coloured my outlook: I was very young and, like all very young folk, very impressionable; and it was the height of the Cold War in which the world, or most of it, acknowledged that there were ‘the Good Guys and the Bad Guys’. For us, ‘the West’ and ‘the Free World’, we were the Good Guys and ‘the ‘Ruskies’ and other ‘Commies’ were the Bad Guys.

Of course, for many it was the other way round: for countries in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and South America where ‘the Ruskies’ and the ‘Commies’ were seen as allies in the struggle against nasty dictatorships, they were seen as the Good Guys, and the putative ‘Free World’ which for purely venal reasons all too often bolstered and often put in place many a nasty dictatorship, they were the Bad Guys.

That gullible ten-year-old, 60-odd years down the line, has learned a lot more history and seen a lot more of life, both personally and at a distance. He no longer believes in black and white, but in infinite shades of grey, with the occasional darker and brighter shades, and the, even less occasional, almost jet-black and almost pure-white spots. This gullible ten-year-old 60-odd years (who if truth be told has had quite an easy, comfortable and happy life) somehow manages down the line to be both cynically pessimistic and agreeably optimistic.

He now knows that ‘America’s’ — and in the United States’s — 1950s outbreak of prosperity and the picture of affluence it was able to purvey throughout much of the world was almost wholly the result of the resurgence of its domestic industries because of World War II. It was a war which was, in a sense, a god-send for the United States. Until Japan — it has to be said inexplicably — attacked Pearl Harbor and the US joined the war, the nation was still largely on its uppers.

Given the vast social discrepancies between the haves and have nots, as great in ‘the land of the free’ as anywhere else despite the faux-patriot insistence than in the ‘land of the free’ anyone could make it, some, many even, were doing quite nicely thank you after a few lean years at the beginning of the 1930s. But a great many more were not and were still scrabbling around for steady work and a steady income to feed their families. For much of the 1930s a staggering one in four men was without a job. But World War II changed all that.

Almost overnight the nation’s factories would be put back to work to produce goods needed for the war effort. And folk again had jobs, a steady income and a future. Until then, though, the US was in parts as much like what we until recently — and patronisingly — referred to as ‘Third World’ countries as were those ‘Third World’ countries. The Northern eastern seaboard states were perhaps in reasonable fettle, but, for example, until ‘that socialist’ Huey Long was elected governor of Louisiana, the whole state had less than 400 miles of tarmacked roads. And the dustbowl of the Mid-West was in an appalling state.

Roosevelt’s first New Deal went some way to alleviating the lives of many at the bottom of the pile, but the nation’s economy was still sluggish and he launched a second New Deal a few years later, giving manual workers rights to join trades unions. But congressional opposition slowly grews — none of the politicians were on there uppers — and the bad times dragged on and remained bad until it was kickstarted by the US entering the war. Then it all changed.

She sheen came off the ‘American Dream’ for those in the ‘free West’ who had observed the country so enviously when the Vietnam War was escalated (a war, incidentally, started by the French, but they rarely get the blame).

Arguably however horrible war is, a case can be made for ‘a just war’. World War II was ‘a just war’. But World War I wasn’t and neither were either the Korean War and the Vietnam War. But it was the latter which really fucked the ‘America’s image’. Timing didn’t help. At the time of the Korean War the West was still in war mode and prepared to die for ‘world peace’. But the late 1960s the WWII survivors were getting on, getting comfortable and getting impatient with their sons and daughters who were as unconvinced by the US’s pious democratic sanctity was we have been ever since.

Those sons and daughters, ironically today’s reactionary generation, refused to play the game, and as more and more of their generation died completely futile deaths in the Far East, they were less and less inclined to help to perpetuate the patriotic myth — as it happened a myth that was less than 30 years old but as a rule folk have short memories — that it was the United States destiny to ‘save the world’. But that’s only one side of the coin.

The other side is a loathsome, offensive, simplistic and widespread knee-jerk anti-Americanism, and it is not restricted to the political left of any country. It is bizarrely quite common. Yet whenever some silly anti-American generalisation is aired there is usually ripply of approval. ‘The Americans are all . . . ‘ What, all of them, all 330 million of them?

On many issues I am the last man to defend many American practices and attitudes. For all its much-touted status as ‘land of the free’, the US as more six times as many of its citizens banged up in jail per head of population than does ‘Red’ China. On the other hand you have a better chance of loudly ranting against the government and staying out of jail or even alive in the US than you do in China. So what does that tell us? Very little, actually, except that the world is a complex place and it is not just stupid but dangerously stupid to try to reduce it to one or two smug certainties. Anyone who thinks she or he understands the world is deluded.

. . .

Several years ago, I read a book which most certainly did not ‘change my life’, but which most certainly did give me a wholly new perspective on the US and, as a result, on the rest of the world. It was Howard Zinn’s admirable A People’s History Of The United States. I have posted about it before and shan’t bother here to repeat myself, but, rather later in life, my eyes were opened to an extent which was long overdue. By that I mean merely that I began fully to understand the complexity of life, humankind and history.

There was much in that book which appalled me as very little had appalled me before. I could and can never again see the United States as a defender of human rights after reading Zinn’s quite sober and unsensational account of the wholesale genocide of what I as a that ten-year-old ‘red indians’ and to whom we now rather more respectfully describe as ‘native Americans’.

Then there are America’s black population. I am at the moment watching Ken Burns’s account of the American Civil War and its purported emancipation of black American slaves, and cannot forget, because of what I read in Zinn’s book, how within just 12 years of the end of the Civil War, blacks were back were they started with the first establishment of the first Jim Crow laws. And from there on — for the next 100 years — it got worse and worse. Take a look to the left. I am no sentimental liberal but since then I cannot hear Billie Holiday’s rendition of the song Strange Fruit without tears coming to my eyes. And I’m as white as chalk. For those who are unfamiliar with it, you can hear it below. And if you didn’t know — but I’m sure you will guess — the ‘strange fruit’ she sings of are the bodies of lynched blacks hanging from the trees.

Zinn makes a very good point in his book about white working class racism. He believes — he claims, I am obliged to write, but I can only say that he makes a great deal of sense for me from what I know of the world — that whipping up hatred of the white underclass against blacks in order to suppress newly emancipated blacks (‘they’re after your jobs!’) was simply a cynical ploy by the ruling class (I can’t believe I’ve used that phrase, but, well, I have because it is true) to kill two birds with one stone.

. . .

All this came to mind — the assumed efficiency and glamour of 1950s America as much as everything else — over these past few days when I read about the complete pig’s ear Donald Trump is making of his country’s response to the coronavirus, the lies he is telling, the confusion he is sowing, the history he is re-writing. Yet apparently as much as his reputation among many in the US is falling — even if it can fall any further — in other quarters it is rising. Those who cheered along the would-be iconoclast who promised them he would ‘drain the Washington swamp’ are convinced that the growing, ever more appalled antagonism towards Trump and how unbelievably ham-fisted he is proving to be is simply more ‘proof’ that ‘they’ are out to get their man. And that thus their man, Trump, somehow must be right.

From what I know of US history the times are not, in fact, exceptionally extraordinary. But what is different is that the world in 2020 is different (as the spread of coronavirus has shown us) than what is was in 1820 or 1920. We smug Brits are half-convinced that when all is said and done those loud, whooping, classless, tacky Yanks have pretty much got a screw loose and not much else can be expected from them. What, though, all of them? All 330 million of them? My one week (!) in the US, a week’s visit to New York in June 1989, was long enough to teach me that however much we Brits think the US is ‘like us’ because we speak the same language, it just ain’t so. It is as much a foreign country as Russia or Tibet. And I suspect that in some ways there are ‘several countries’ even within the US — just how much to Texans have in common with the folk in Maine, for example?

The main difference the US makes to the world is by virtue of its size and the size of its economy. But that is a hell of a difference. And because of the impact it has the world, and not just the US, really does not need a total idiot like Trump in charge. The sad thing is there’s bugger all we can do about it.

Might I end on a plea: if you feel that despite my pious disclaimer I am also guilty of knee-jerk anti-Americanism, can I urge you to accept that I am not, that the impression is merely conveyed by this piece not being as well written as it might have been?

At least two things were at play here and coloured my outlook: I was very young and, like all very young folk, very impressionable; and it was the height of the Cold War in which the world, or most of it, acknowledged that there were ‘the Good Guys and the Bad Guys’. For us, ‘the West’ and ‘the Free World’, we were the Good Guys and ‘the ‘Ruskies’ and other ‘Commies’ were the Bad Guys.

Of course, for many it was the other way round: for countries in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and South America where ‘the Ruskies’ and the ‘Commies’ were seen as allies in the struggle against nasty dictatorships, they were seen as the Good Guys, and the putative ‘Free World’ which for purely venal reasons all too often bolstered and often put in place many a nasty dictatorship, they were the Bad Guys.

That gullible ten-year-old, 60-odd years down the line, has learned a lot more history and seen a lot more of life, both personally and at a distance. He no longer believes in black and white, but in infinite shades of grey, with the occasional darker and brighter shades, and the, even less occasional, almost jet-black and almost pure-white spots. This gullible ten-year-old 60-odd years (who if truth be told has had quite an easy, comfortable and happy life) somehow manages down the line to be both cynically pessimistic and agreeably optimistic.

He now knows that ‘America’s’ — and in the United States’s — 1950s outbreak of prosperity and the picture of affluence it was able to purvey throughout much of the world was almost wholly the result of the resurgence of its domestic industries because of World War II. It was a war which was, in a sense, a god-send for the United States. Until Japan — it has to be said inexplicably — attacked Pearl Harbor and the US joined the war, the nation was still largely on its uppers.

Given the vast social discrepancies between the haves and have nots, as great in ‘the land of the free’ as anywhere else despite the faux-patriot insistence than in the ‘land of the free’ anyone could make it, some, many even, were doing quite nicely thank you after a few lean years at the beginning of the 1930s. But a great many more were not and were still scrabbling around for steady work and a steady income to feed their families. For much of the 1930s a staggering one in four men was without a job. But World War II changed all that.

Almost overnight the nation’s factories would be put back to work to produce goods needed for the war effort. And folk again had jobs, a steady income and a future. Until then, though, the US was in parts as much like what we until recently — and patronisingly — referred to as ‘Third World’ countries as were those ‘Third World’ countries. The Northern eastern seaboard states were perhaps in reasonable fettle, but, for example, until ‘that socialist’ Huey Long was elected governor of Louisiana, the whole state had less than 400 miles of tarmacked roads. And the dustbowl of the Mid-West was in an appalling state.

Roosevelt’s first New Deal went some way to alleviating the lives of many at the bottom of the pile, but the nation’s economy was still sluggish and he launched a second New Deal a few years later, giving manual workers rights to join trades unions. But congressional opposition slowly grews — none of the politicians were on there uppers — and the bad times dragged on and remained bad until it was kickstarted by the US entering the war. Then it all changed.

She sheen came off the ‘American Dream’ for those in the ‘free West’ who had observed the country so enviously when the Vietnam War was escalated (a war, incidentally, started by the French, but they rarely get the blame).

Arguably however horrible war is, a case can be made for ‘a just war’. World War II was ‘a just war’. But World War I wasn’t and neither were either the Korean War and the Vietnam War. But it was the latter which really fucked the ‘America’s image’. Timing didn’t help. At the time of the Korean War the West was still in war mode and prepared to die for ‘world peace’. But the late 1960s the WWII survivors were getting on, getting comfortable and getting impatient with their sons and daughters who were as unconvinced by the US’s pious democratic sanctity was we have been ever since.

Those sons and daughters, ironically today’s reactionary generation, refused to play the game, and as more and more of their generation died completely futile deaths in the Far East, they were less and less inclined to help to perpetuate the patriotic myth — as it happened a myth that was less than 30 years old but as a rule folk have short memories — that it was the United States destiny to ‘save the world’. But that’s only one side of the coin.

The other side is a loathsome, offensive, simplistic and widespread knee-jerk anti-Americanism, and it is not restricted to the political left of any country. It is bizarrely quite common. Yet whenever some silly anti-American generalisation is aired there is usually ripply of approval. ‘The Americans are all . . . ‘ What, all of them, all 330 million of them?

On many issues I am the last man to defend many American practices and attitudes. For all its much-touted status as ‘land of the free’, the US as more six times as many of its citizens banged up in jail per head of population than does ‘Red’ China. On the other hand you have a better chance of loudly ranting against the government and staying out of jail or even alive in the US than you do in China. So what does that tell us? Very little, actually, except that the world is a complex place and it is not just stupid but dangerously stupid to try to reduce it to one or two smug certainties. Anyone who thinks she or he understands the world is deluded.

. . .

There was much in that book which appalled me as very little had appalled me before. I could and can never again see the United States as a defender of human rights after reading Zinn’s quite sober and unsensational account of the wholesale genocide of what I as a that ten-year-old ‘red indians’ and to whom we now rather more respectfully describe as ‘native Americans’.

Then there are America’s black population. I am at the moment watching Ken Burns’s account of the American Civil War and its purported emancipation of black American slaves, and cannot forget, because of what I read in Zinn’s book, how within just 12 years of the end of the Civil War, blacks were back were they started with the first establishment of the first Jim Crow laws. And from there on — for the next 100 years — it got worse and worse. Take a look to the left. I am no sentimental liberal but since then I cannot hear Billie Holiday’s rendition of the song Strange Fruit without tears coming to my eyes. And I’m as white as chalk. For those who are unfamiliar with it, you can hear it below. And if you didn’t know — but I’m sure you will guess — the ‘strange fruit’ she sings of are the bodies of lynched blacks hanging from the trees.

Zinn makes a very good point in his book about white working class racism. He believes — he claims, I am obliged to write, but I can only say that he makes a great deal of sense for me from what I know of the world — that whipping up hatred of the white underclass against blacks in order to suppress newly emancipated blacks (‘they’re after your jobs!’) was simply a cynical ploy by the ruling class (I can’t believe I’ve used that phrase, but, well, I have because it is true) to kill two birds with one stone.

. . .

All this came to mind — the assumed efficiency and glamour of 1950s America as much as everything else — over these past few days when I read about the complete pig’s ear Donald Trump is making of his country’s response to the coronavirus, the lies he is telling, the confusion he is sowing, the history he is re-writing. Yet apparently as much as his reputation among many in the US is falling — even if it can fall any further — in other quarters it is rising. Those who cheered along the would-be iconoclast who promised them he would ‘drain the Washington swamp’ are convinced that the growing, ever more appalled antagonism towards Trump and how unbelievably ham-fisted he is proving to be is simply more ‘proof’ that ‘they’ are out to get their man. And that thus their man, Trump, somehow must be right.

From what I know of US history the times are not, in fact, exceptionally extraordinary. But what is different is that the world in 2020 is different (as the spread of coronavirus has shown us) than what is was in 1820 or 1920. We smug Brits are half-convinced that when all is said and done those loud, whooping, classless, tacky Yanks have pretty much got a screw loose and not much else can be expected from them. What, though, all of them? All 330 million of them? My one week (!) in the US, a week’s visit to New York in June 1989, was long enough to teach me that however much we Brits think the US is ‘like us’ because we speak the same language, it just ain’t so. It is as much a foreign country as Russia or Tibet. And I suspect that in some ways there are ‘several countries’ even within the US — just how much to Texans have in common with the folk in Maine, for example?

The main difference the US makes to the world is by virtue of its size and the size of its economy. But that is a hell of a difference. And because of the impact it has the world, and not just the US, really does not need a total idiot like Trump in charge. The sad thing is there’s bugger all we can do about it.

Might I end on a plea: if you feel that despite my pious disclaimer I am also guilty of knee-jerk anti-Americanism, can I urge you to accept that I am not, that the impression is merely conveyed by this piece not being as well written as it might have been?

Thursday 26 March 2020

We have nothing to fear except fear itself (and, of course, running out of loo roll, sugar, milk, shampoo, those tasty little choc things, coffee beans, the Radio Times, a back-up iPhone, porn mags and I really don’t know what else, but not having those scares me shitless!)

I’ve got out of the habit a little of posting here and I don’t know why. It’s not as though I don’t think of things to write about, but what with all the bloody reading of books about Hemingway and knowing that if I should be writing anything, it should be first drafts of the different elements that will go to make up the long blog I’m planning,

I don’t seem to get around to this blog (and I have got quite a bit of the Hemingway words done already, though I must fight the tendency to re-write and hone stuff I’ve already written instead of writing new stuff). There is one question, though, which has brought me back to this blog and it has — so bloody inevitably — to do with the global coronavirus pandemic.

I’ve long thought (as, I’m sure, have many others, although I haven’t yet heard much on TV and the radio or read much in the papers) that the true danger from the pandemic is not to our health, but to various global economies. It will damage them enormously, and after folk have stopped catching the virus and often dying from it, the effects of the pandemic will long be felt.

In short, in order to counter the spread of the virus many countries in the northern hemisphere have simply closed down, insisting everyone isolate themselves at home unless it is absolutely necessary that they go out. Don’t go to work, everyone has been told, and only go out briefly if you have to go shopping or pick up a prescription.

As for thus having no income, there are various government guaranteeing wages (somehow — I’m very unclear as to the details or how the schemes will work). Here in Britain it is even trying to find some way of guaranteeing that the self-employed don’t lose out either, a far trickier task. Businesses, who must also shut up shop, have been told that they, too, will get ‘government help’.

It all sounds fine and dandy, and even this grubby little cynic is impressed who, broadly, everyone is coming together for the sake of everyone else. Yesterday, I went out for the first time in several days — I am now retired and have not had to worry about income as my pension should not be affected — to the St Breward Store and Post Office (at the top of the village by the church and next to the Old Inn if you ever find yourself in this neck of the woods) and was puzzled to find six individuals standing alone in the pub car park, randomly in no particular order. They were, or seemed to be, just standing about. It turned out that only one customer was allowed into the shop at a time, and this was ‘the queue’, though as all were at least eight feet from anyone else it looked bugger all like any queue I have ever seen (and joined).

Quite whether that measure — keeping our distance in a pub car on the very rural North Cornwall Moor — is as useful as not travelling by crowded tube, commuter train or bus in a busy city, is a moot point. But as Tesco say

‘every little helps’, and — well, why not? We might eventually discover that ‘social distancing’ was about as useful as ‘hiding under a table in the event of a nuclear attack’. But until then . . .

It is March 26, 2020, today, and we have been assured that the pandemic will not be over soon and could last until well into June (Wimbledon will decide by next week whether to postpone this year’s tournament). So I have no rational reason for saying this and shan’t pretend I do: but I have a gut feeling the emergency will be over sooner rather than later. I might, of course, look very silly indeed to someone reading this in six months or a year’s time. All I am saying is that is my gut feeling, for better or worse and for what it’s worth. The knock-on effects, though, I suspect will be felt for month and possibly years. But, fingers crossed, there might even be some positive developments.

Ever since, first Wuhan, then Lombardy, now most all European countries have been in lockdown and folk are not going out (and, crucially, not commuting), air pollution has fallen dramatically as have CO2 levels. Now you might be a ‘man-made climate change’ freak or you might be an out-and-out denier, but that fact, the fall in air pollution and CO2 levels cannot be denied and has to be pertinent. The obvious conclusion is for us all to carry on ‘not commuting’. That, though, is not possible. Or might it be? Might this now not be an opportunity, given such dramatic evidence of how we can drastically cut air pollution and CO2 levels, for wholesale reassessment of how our economies are set up? Of course, it is, but it’s easier said than done.

My former employer, the Daily Mail, operates from Northcliffe House in Kensington, West London, and I should imagine that what with all the other departments involved in the operation of producing a newspaper — folk usually think in terms of ‘writer and reporters’ but, in fact, not only are there sub-editors busying themselves on the editorial side, but their work would simply not be possible if it weren’t for a range of other departments: advertising and marketing, promotions, personnel, finance and — not least — the IT department.

IT must get an especial mention: like every other pen-pushing industry in the 21st century, IT keep the show on the road. Any glitch has to be sorted out in minutes. And it always is. But over these past few weeks they have (former colleagues tell me) excelled themselves. Why? Because Northcliffe House is now completely empty and will be for the duration. Everyone is working from home (as I did when I was still placing the puzzles). Logging on remotely to the system is straightforward, but when I was doing it just a few did it regularly, certainly not more than 1,000 bods. So the system had and has to be robust and IT have to be on top of it 24/7. And they were and are.

But the Mail is, in a sense, lucky. Newspapers, in a way, operate on the fringes to mainstream pen-pushing companies. By the nature of their industry and what they do, they are accustomed and usually prepared to adopt and adapt to changing circumstances almost overnight (the paper is largely printed in East London, but they have an identical twin operation ready to take over at a moments notice for the paper to be printed in Didcot, just under 100 miles to the west).

I don’t think other industries are as flexible and, getting back to the bad knock-on effects of the pandemic, smaller companies, of which there are thousands throughout Europe simply can’t afford to shut down for a month or two. Once they shut down and have no cashflow they go bust and thousand, quite possibly millions, of jobs are lost.

I have seen warnings that we might be in for a worldwide recession: a ‘global economy’ smug economists boasted about 20 years ago which would, and has, distribute ever more prosperity to ever more people in ever more countries has a downside: problems travel equally as fast. If — and it can only be an ‘if’ — there is such a recession it will be deeper and last longer than anything since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

There are also claims that because of the social effects of widespread unemployment, it might have been better to let the pandemic take its course. And catastrophic economic conditions invariably play out in politics. Just how keen will Europe’s liberally minded folk be to look on the camps of several thousand migrants to the EU from

North Africa and the Middle East if they are out of a job with little prospect of getting another, falling into debt and are forced to sell their homes for less then they are worth? Rather less than they were last year, and last year they were rather less inclined to brotherly love than they were 15 years ago. In the context of the EU, it is also worth considering just what effect on the euro — the always rather flakey euro which has never quite found its feet — a collapse in the economies of Spain and Italy would have.

Naturally, on that and other questions there can only be opinions. There cannot be ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ answers. Similarly, the prognostications of various ‘health bodies’ as how the pandemic will pan out are, at the end of the day, less copper-bottomed than they might be (and their supporters claim).

All are based on ‘computer modelling’ — ‘if this, then what?’ — and it depends upon what data you start with, for which read, to put it more brutally, what assumptions you make. So the results will vary, and, for example, just a few days ago ‘Oxford’s Evolutionary Ecology of Infectious Disease group’ suggested (here is one report) that perhaps things weren’t quite as bad as they seemed. It’s ‘model’ suggested that more than half of Britain’s population had been infected by the Covid-19 with no serious effects, in many quite mild effect.

If true, that suggested coronavirus was not half as dangerous or lethal as had so far been feared. This conclusion from one ‘health body’, though, is at odds with previous conclusions from other ‘health bodies’ and has been criticised and downplayed. So who is right? I don’t know, I can’t know, and nor do you or can you. At the end of the day you pays your money and you makes your choice. And that is all a tad pointless.

As for what effects the universal closing down of the economy will have in the coming months and years, who knows. (As I’ve recorded in this blog before: one definition of an economist is someone who can utterly convincingly explain this week why what he had utterly convincingly predicted last week didn’t actually happen.) But as I began this blog entry, I’ll end it: I suspect the future has less to fear from coronavirus medically than it does from the effects socially and economically of measures taken to counter its spread.

. . .

And just for good measure . . .

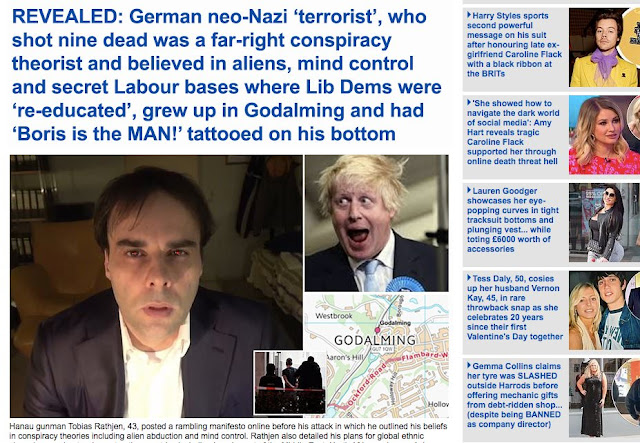

This one has got bugger all to do with what I am writing about, but I like it. It is just a screenshot I took while watchign a documentary and which I then dicked around with briefly in Photoshop.

I don’t seem to get around to this blog (and I have got quite a bit of the Hemingway words done already, though I must fight the tendency to re-write and hone stuff I’ve already written instead of writing new stuff). There is one question, though, which has brought me back to this blog and it has — so bloody inevitably — to do with the global coronavirus pandemic.

I’ve long thought (as, I’m sure, have many others, although I haven’t yet heard much on TV and the radio or read much in the papers) that the true danger from the pandemic is not to our health, but to various global economies. It will damage them enormously, and after folk have stopped catching the virus and often dying from it, the effects of the pandemic will long be felt.

In short, in order to counter the spread of the virus many countries in the northern hemisphere have simply closed down, insisting everyone isolate themselves at home unless it is absolutely necessary that they go out. Don’t go to work, everyone has been told, and only go out briefly if you have to go shopping or pick up a prescription.

As for thus having no income, there are various government guaranteeing wages (somehow — I’m very unclear as to the details or how the schemes will work). Here in Britain it is even trying to find some way of guaranteeing that the self-employed don’t lose out either, a far trickier task. Businesses, who must also shut up shop, have been told that they, too, will get ‘government help’.

It all sounds fine and dandy, and even this grubby little cynic is impressed who, broadly, everyone is coming together for the sake of everyone else. Yesterday, I went out for the first time in several days — I am now retired and have not had to worry about income as my pension should not be affected — to the St Breward Store and Post Office (at the top of the village by the church and next to the Old Inn if you ever find yourself in this neck of the woods) and was puzzled to find six individuals standing alone in the pub car park, randomly in no particular order. They were, or seemed to be, just standing about. It turned out that only one customer was allowed into the shop at a time, and this was ‘the queue’, though as all were at least eight feet from anyone else it looked bugger all like any queue I have ever seen (and joined).

Quite whether that measure — keeping our distance in a pub car on the very rural North Cornwall Moor — is as useful as not travelling by crowded tube, commuter train or bus in a busy city, is a moot point. But as Tesco say

‘every little helps’, and — well, why not? We might eventually discover that ‘social distancing’ was about as useful as ‘hiding under a table in the event of a nuclear attack’. But until then . . .

It is March 26, 2020, today, and we have been assured that the pandemic will not be over soon and could last until well into June (Wimbledon will decide by next week whether to postpone this year’s tournament). So I have no rational reason for saying this and shan’t pretend I do: but I have a gut feeling the emergency will be over sooner rather than later. I might, of course, look very silly indeed to someone reading this in six months or a year’s time. All I am saying is that is my gut feeling, for better or worse and for what it’s worth. The knock-on effects, though, I suspect will be felt for month and possibly years. But, fingers crossed, there might even be some positive developments.

Ever since, first Wuhan, then Lombardy, now most all European countries have been in lockdown and folk are not going out (and, crucially, not commuting), air pollution has fallen dramatically as have CO2 levels. Now you might be a ‘man-made climate change’ freak or you might be an out-and-out denier, but that fact, the fall in air pollution and CO2 levels cannot be denied and has to be pertinent. The obvious conclusion is for us all to carry on ‘not commuting’. That, though, is not possible. Or might it be? Might this now not be an opportunity, given such dramatic evidence of how we can drastically cut air pollution and CO2 levels, for wholesale reassessment of how our economies are set up? Of course, it is, but it’s easier said than done.

My former employer, the Daily Mail, operates from Northcliffe House in Kensington, West London, and I should imagine that what with all the other departments involved in the operation of producing a newspaper — folk usually think in terms of ‘writer and reporters’ but, in fact, not only are there sub-editors busying themselves on the editorial side, but their work would simply not be possible if it weren’t for a range of other departments: advertising and marketing, promotions, personnel, finance and — not least — the IT department.

IT must get an especial mention: like every other pen-pushing industry in the 21st century, IT keep the show on the road. Any glitch has to be sorted out in minutes. And it always is. But over these past few weeks they have (former colleagues tell me) excelled themselves. Why? Because Northcliffe House is now completely empty and will be for the duration. Everyone is working from home (as I did when I was still placing the puzzles). Logging on remotely to the system is straightforward, but when I was doing it just a few did it regularly, certainly not more than 1,000 bods. So the system had and has to be robust and IT have to be on top of it 24/7. And they were and are.

But the Mail is, in a sense, lucky. Newspapers, in a way, operate on the fringes to mainstream pen-pushing companies. By the nature of their industry and what they do, they are accustomed and usually prepared to adopt and adapt to changing circumstances almost overnight (the paper is largely printed in East London, but they have an identical twin operation ready to take over at a moments notice for the paper to be printed in Didcot, just under 100 miles to the west).

I don’t think other industries are as flexible and, getting back to the bad knock-on effects of the pandemic, smaller companies, of which there are thousands throughout Europe simply can’t afford to shut down for a month or two. Once they shut down and have no cashflow they go bust and thousand, quite possibly millions, of jobs are lost.

I have seen warnings that we might be in for a worldwide recession: a ‘global economy’ smug economists boasted about 20 years ago which would, and has, distribute ever more prosperity to ever more people in ever more countries has a downside: problems travel equally as fast. If — and it can only be an ‘if’ — there is such a recession it will be deeper and last longer than anything since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

There are also claims that because of the social effects of widespread unemployment, it might have been better to let the pandemic take its course. And catastrophic economic conditions invariably play out in politics. Just how keen will Europe’s liberally minded folk be to look on the camps of several thousand migrants to the EU from

North Africa and the Middle East if they are out of a job with little prospect of getting another, falling into debt and are forced to sell their homes for less then they are worth? Rather less than they were last year, and last year they were rather less inclined to brotherly love than they were 15 years ago. In the context of the EU, it is also worth considering just what effect on the euro — the always rather flakey euro which has never quite found its feet — a collapse in the economies of Spain and Italy would have.

Naturally, on that and other questions there can only be opinions. There cannot be ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ answers. Similarly, the prognostications of various ‘health bodies’ as how the pandemic will pan out are, at the end of the day, less copper-bottomed than they might be (and their supporters claim).

All are based on ‘computer modelling’ — ‘if this, then what?’ — and it depends upon what data you start with, for which read, to put it more brutally, what assumptions you make. So the results will vary, and, for example, just a few days ago ‘Oxford’s Evolutionary Ecology of Infectious Disease group’ suggested (here is one report) that perhaps things weren’t quite as bad as they seemed. It’s ‘model’ suggested that more than half of Britain’s population had been infected by the Covid-19 with no serious effects, in many quite mild effect.

If true, that suggested coronavirus was not half as dangerous or lethal as had so far been feared. This conclusion from one ‘health body’, though, is at odds with previous conclusions from other ‘health bodies’ and has been criticised and downplayed. So who is right? I don’t know, I can’t know, and nor do you or can you. At the end of the day you pays your money and you makes your choice. And that is all a tad pointless.

As for what effects the universal closing down of the economy will have in the coming months and years, who knows. (As I’ve recorded in this blog before: one definition of an economist is someone who can utterly convincingly explain this week why what he had utterly convincingly predicted last week didn’t actually happen.) But as I began this blog entry, I’ll end it: I suspect the future has less to fear from coronavirus medically than it does from the effects socially and economically of measures taken to counter its spread.

. . .

And just for good measure . . .

This one has got bugger all to do with what I am writing about, but I like it. It is just a screenshot I took while watchign a documentary and which I then dicked around with briefly in Photoshop.

Friday 13 March 2020

Thursday 5 March 2020

. . . the fact is, nothing much changes, and an older generation will always sooner or later get the two-fingered salute (just as they gave it to their mums and dads)

If for whatever reason — it could be frustration, simple boredom or just malice — you want to end a discussion in its tracks, the ruse to use is to announce ‘well, it really does depend on what you mean by . . .’ It works every time.

First of all, the discussion itself is immediately diverted from its original course, and from there on in it is the simplest of tasks to muddy the waters to such an extent that everyone taking part, all intent on promoting their own take on whatever is being discussed and rarely having the patience and tolerance, let alone the good manners, to listen to the views of others loses interest; and, metaphorically, they wander off.

The irony, of course, is that it is true: it really does depend on ‘what you mean by . . .’ It really does matter that what is understood by a word or idea is crucial to any discussion of that idea; and if we are all working on a different understanding, any discussion becomes more than a little pointless. Yet all too often those involved in such discussion are simply unaware that the others don’t understand that concept in the same way.

A good, though undoubtedly hoary first-year-of-philosophy example is the notion of ‘freedom’: does it mean ‘free to’ or ‘free from’? In some situations, of course, they might coincide — if I live in a society ‘free from’ tyranny, I am ‘free to’ speak my mind without concern for my safety. In others, though, the distinction is crucial.

If someone were to claim that it is crucial ‘that we all have our freedom’, you might then ask him or her whether or not that would cover the freedom of a paedophile to indulge in sexual activity with a child. The likely response to that would be ‘of course not, it must be freedom to act and behave within the bounds of our established morality’. Well, quite, but by then — within a very brief ten seconds — you have already taken a diversion from the main discussion.

Certainly, the bounds and dictates of the morality prevalent in any given culture have a bearing on what we are ‘free to do’, but by now we are no longer discussing the notion of ‘freedom’ in abstract (as we thought we were) but already limiting ourselves to the notion of ‘freedom’ in our particular culture. And that is more of a practical matter than philosophical.

I got to be thinking along those lines when, plodding on with this bloody Hemingway project (which, contrary to what you might gather from my description of it as ‘this bloody Hemingway project’, I am still enjoying although almost by the hour the task seems to get bigger and bigger) I got to a point where I decided the best and simplest way forward is to look at the man, his life and his work a little more obliquely, to consider various related matter.

So, for example . . .

Some time ago I came across the review by Virginia Woolf of Hemingway’s second volume of short stories. It is, though, more an essay by Woolf on critics and criticism. In it she makes some good points, not least that most of us, almost despite ourselves, regard ‘the critics’ as somehow better informed and more qualified to pass judgment than we are (and wonders why). You can read her piece here, but her introduction sums it up well:

Human credulity is indeed wonderful. There may be good reasons for believing in a King or a Judge or a Lord Mayor. When we see them go sweeping by in their robes and their wigs, with their heralds and their outriders, our knees begin to shake and our looks to falter. But what reason there is for believing in critics it is impossible to say. They have neither wigs nor outriders. They differ in no way from other people if one sees them in the flesh. Yet these insignificant fellow creatures have only to shut themselves up in a room, dip a pen in the ink, and call themselves ‘we’, for the rest of us to believe that they are somehow exalted, inspired, infallible. Wigs grow on their heads. Robes cover their limbs. No greater miracle was ever performed by the power of human credulity.

Perhaps her observation rings a bell with you. It certainly did with me. And I wonder how many of us settle for simply adopting wholesale as our own the verdict of a critic (and, of course, then pontificate loudly about the book or writer in question as though we knew what we were talking about) for no good reason than that she or he is ‘the New York Times/The Observer/The Sunday Times/the Washington Post reviewer?

So in this Hemingway bollocks I decided to consider different questions in relation to Hemingway rather than just approach him and his work four-square. That approach also has the virtue of not having to plough my way through all his bloody work and just stick to the three volumes of short stories and his first three novels. Death In The Afternoon, The Green Hills Of Summer, Across The River And Into The Hills and the rest? Fuck off. I’ve read enough reviews of them to know when enough is enough.

So, in relation to Woolf’s essay, I’ve decided, for example, to consider the notions of ‘subjectivity’ and ‘objectivity’, as in ‘can there really be an “objective judgment” of a work by Hemingway (or any other writer for that matter)?’ And if we line up all the critics in their underwear and strip them of their robes and wigs, just how much more ‘valid’ are their verdicts than yours or mine?

Then there’s the question of what are we supposed to make of the fact that critics disagree with each other in their judgments of a novel, exhibition, play or film? Who is ‘right’ and who is ‘wrong’?

From there it was just a short skip and a jump to realising — or, more cautiously, coming to the conclusion — that there is no ‘objectivity’ in criticism because there simply cannot be. Each judgment is subjective, like it or not. Granted, a critic is probably better read than you or I, but her or his judgment, at the end of the day, is still a subjective one. And, strictly, no number of such ‘subjective’ judgments, however much they agree with each other, add up to one ‘objective’ judgment — ‘the critics are all agreed’ merely means ‘the critics are all agreed’. It doesn’t necessarily mean ‘the critics are all right’.

A further complication, though I make this point merely by the by, is that different generations favour different styles and, furthermore, each ‘new generation’, keen to put as much clear blue water between itself and its parent generation, will favour books, music, films and fashions as different from those popular with its parent generation as possible.

That, I shall be suggesting when I post my Hemingway project (are preliminary post is here, though what I have posted there has since been cut by two-thirds to make way for a prologue) is one essential factor in the rise of Hemingway to prominence. (Would the rise of ‘conceptual art’ really have occurred if its quintessence wasn’t sticking up two fingers (US ‘the middle finger) at the previous generation?

So with Hemingway, no one had before used the words ‘damn’ and ‘bitch’ in print, for example, or had the novels characters getting rat-arsed and sleeping around, and the dizzy, hedonistic young folk of the Jazz Age, as keen to upset the older generation as they were to have a great time loved it. Just loved it.

Another aspect I want to take a look at is ‘modernism’ and more specifically Hemingway’s modernism. What it might be? Like many other things, we — well, more modestly, I — think we ‘know’ something, but when we begin to consider what it is we ‘know’, we realise we know close to fuck-all about it.

Hemingway is often talked of as a ‘modernist’ writer, but from where I sit (and I am really not as well-read as I might be to make such a point, but . . . ) there seems to me less ‘modernist’ about him than there was about Ford Madox Ford, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and later Virginia Woolf. But what is modernism? How is it defined?

I’ve always assumed that ‘modernists’ were working from some underlying philosophy or aesthetic theory, but how true is that? Were they? Was it necessary? From what I know of Hemingway’s views, there wasn’t much theorising, and even his much-quoted ‘iceberg theory’ is, to be frank, essentially pretty threadbare and, as he states it, middlebrow Sunday supplement stuff.

One very obvious point, which has been made several times by others, is to ask why he thought his ‘theory of omission’ was so ‘new’ or even revolutionary when for many years writers had been composing their work specifically to allow and encourage their readers to ‘read between the lines’. We, the readers, read between the lines, for example, in Hemingway’s story Hills Like White Elephants and gather a guy is trying to persuade his gal to have an abortion. But ‘writing between the lines’ (if you see what I mean), is also something writers of fiction had been doing long before that story was written.

A Hemingway freak might counter that ‘that isn’t what Hemingway meant’ by his ‘theory of omission’, to which I would counter-counter that if Hemingway did mean what he seems to have meant — that ‘you could omit anything . . . and the omitted part would strengthen the story’ — he was kidding no one but himself if he meant that he could leave out a detail completely and I mean completely (like the suicide in the oft-given example of his story Out Of Season), but that the reader would somehow still ‘pick up’ on that detail. It’s all just a tad too pseudo-metaphysical for me. Or perhaps I have got it wrong and he doesn’t quite mean that, either.

Certainly, many of his stories were not ‘about’ what they were ostensibly ‘about’, but that has been the essence of interesting and engaging fiction for many years before young Ernie first put pen to paper. Why did he think he had hit upon something new?

On the question of ‘Hemingway’s modernism’, it is also worth mentioning that he was notoriously, not to say very ostentatiously, anti-intellectual. There are suggestions that, much like his very ostentatious and increasingly unconvincing displays of machismo, the anti-intellectualism was something of a front.

One friend from on the Toronto Star, Greg Clark, who had known him when he first turned up in Toronto in 1919, remarked when he returned to the paper in 1923 for a staff job after freelancing in Paris (for what turned out to just a few months): ‘A more weird combination of quivering sensitiveness and preoccupation with violence never walked this earth’. But whatever the reason for it, Hemingway was remarkably reluctant to discuss intellectual matters.

His friend in Paris (and later until, invariably and inevitably, Hemingway fell out with him) Archibald McLeish remembered many occasions when he attempted to start a discussion and tease out Hemingway’s thoughts on aesthetics and related matters, only for the great man swiftly to change the subject to hunting or fishing or boxing or bullfighting or some such topic.

For me the task is now to learn a lot more about ‘modernism’. But at least I now realise I know next to bugger all, so that’s a start of sorts.

Pip, pip.

Here’s a bit of modernism for you to keep you happy . . .

First of all, the discussion itself is immediately diverted from its original course, and from there on in it is the simplest of tasks to muddy the waters to such an extent that everyone taking part, all intent on promoting their own take on whatever is being discussed and rarely having the patience and tolerance, let alone the good manners, to listen to the views of others loses interest; and, metaphorically, they wander off.

The irony, of course, is that it is true: it really does depend on ‘what you mean by . . .’ It really does matter that what is understood by a word or idea is crucial to any discussion of that idea; and if we are all working on a different understanding, any discussion becomes more than a little pointless. Yet all too often those involved in such discussion are simply unaware that the others don’t understand that concept in the same way.

A good, though undoubtedly hoary first-year-of-philosophy example is the notion of ‘freedom’: does it mean ‘free to’ or ‘free from’? In some situations, of course, they might coincide — if I live in a society ‘free from’ tyranny, I am ‘free to’ speak my mind without concern for my safety. In others, though, the distinction is crucial.

If someone were to claim that it is crucial ‘that we all have our freedom’, you might then ask him or her whether or not that would cover the freedom of a paedophile to indulge in sexual activity with a child. The likely response to that would be ‘of course not, it must be freedom to act and behave within the bounds of our established morality’. Well, quite, but by then — within a very brief ten seconds — you have already taken a diversion from the main discussion.

Certainly, the bounds and dictates of the morality prevalent in any given culture have a bearing on what we are ‘free to do’, but by now we are no longer discussing the notion of ‘freedom’ in abstract (as we thought we were) but already limiting ourselves to the notion of ‘freedom’ in our particular culture. And that is more of a practical matter than philosophical.

I got to be thinking along those lines when, plodding on with this bloody Hemingway project (which, contrary to what you might gather from my description of it as ‘this bloody Hemingway project’, I am still enjoying although almost by the hour the task seems to get bigger and bigger) I got to a point where I decided the best and simplest way forward is to look at the man, his life and his work a little more obliquely, to consider various related matter.

So, for example . . .

Some time ago I came across the review by Virginia Woolf of Hemingway’s second volume of short stories. It is, though, more an essay by Woolf on critics and criticism. In it she makes some good points, not least that most of us, almost despite ourselves, regard ‘the critics’ as somehow better informed and more qualified to pass judgment than we are (and wonders why). You can read her piece here, but her introduction sums it up well:

Human credulity is indeed wonderful. There may be good reasons for believing in a King or a Judge or a Lord Mayor. When we see them go sweeping by in their robes and their wigs, with their heralds and their outriders, our knees begin to shake and our looks to falter. But what reason there is for believing in critics it is impossible to say. They have neither wigs nor outriders. They differ in no way from other people if one sees them in the flesh. Yet these insignificant fellow creatures have only to shut themselves up in a room, dip a pen in the ink, and call themselves ‘we’, for the rest of us to believe that they are somehow exalted, inspired, infallible. Wigs grow on their heads. Robes cover their limbs. No greater miracle was ever performed by the power of human credulity.

Perhaps her observation rings a bell with you. It certainly did with me. And I wonder how many of us settle for simply adopting wholesale as our own the verdict of a critic (and, of course, then pontificate loudly about the book or writer in question as though we knew what we were talking about) for no good reason than that she or he is ‘the New York Times/The Observer/The Sunday Times/the Washington Post reviewer?

So in this Hemingway bollocks I decided to consider different questions in relation to Hemingway rather than just approach him and his work four-square. That approach also has the virtue of not having to plough my way through all his bloody work and just stick to the three volumes of short stories and his first three novels. Death In The Afternoon, The Green Hills Of Summer, Across The River And Into The Hills and the rest? Fuck off. I’ve read enough reviews of them to know when enough is enough.

So, in relation to Woolf’s essay, I’ve decided, for example, to consider the notions of ‘subjectivity’ and ‘objectivity’, as in ‘can there really be an “objective judgment” of a work by Hemingway (or any other writer for that matter)?’ And if we line up all the critics in their underwear and strip them of their robes and wigs, just how much more ‘valid’ are their verdicts than yours or mine?

Then there’s the question of what are we supposed to make of the fact that critics disagree with each other in their judgments of a novel, exhibition, play or film? Who is ‘right’ and who is ‘wrong’?

From there it was just a short skip and a jump to realising — or, more cautiously, coming to the conclusion — that there is no ‘objectivity’ in criticism because there simply cannot be. Each judgment is subjective, like it or not. Granted, a critic is probably better read than you or I, but her or his judgment, at the end of the day, is still a subjective one. And, strictly, no number of such ‘subjective’ judgments, however much they agree with each other, add up to one ‘objective’ judgment — ‘the critics are all agreed’ merely means ‘the critics are all agreed’. It doesn’t necessarily mean ‘the critics are all right’.

A further complication, though I make this point merely by the by, is that different generations favour different styles and, furthermore, each ‘new generation’, keen to put as much clear blue water between itself and its parent generation, will favour books, music, films and fashions as different from those popular with its parent generation as possible.

That, I shall be suggesting when I post my Hemingway project (are preliminary post is here, though what I have posted there has since been cut by two-thirds to make way for a prologue) is one essential factor in the rise of Hemingway to prominence. (Would the rise of ‘conceptual art’ really have occurred if its quintessence wasn’t sticking up two fingers (US ‘the middle finger) at the previous generation?

So with Hemingway, no one had before used the words ‘damn’ and ‘bitch’ in print, for example, or had the novels characters getting rat-arsed and sleeping around, and the dizzy, hedonistic young folk of the Jazz Age, as keen to upset the older generation as they were to have a great time loved it. Just loved it.

Another aspect I want to take a look at is ‘modernism’ and more specifically Hemingway’s modernism. What it might be? Like many other things, we — well, more modestly, I — think we ‘know’ something, but when we begin to consider what it is we ‘know’, we realise we know close to fuck-all about it.

Hemingway is often talked of as a ‘modernist’ writer, but from where I sit (and I am really not as well-read as I might be to make such a point, but . . . ) there seems to me less ‘modernist’ about him than there was about Ford Madox Ford, Ezra Pound, James Joyce and later Virginia Woolf. But what is modernism? How is it defined?

I’ve always assumed that ‘modernists’ were working from some underlying philosophy or aesthetic theory, but how true is that? Were they? Was it necessary? From what I know of Hemingway’s views, there wasn’t much theorising, and even his much-quoted ‘iceberg theory’ is, to be frank, essentially pretty threadbare and, as he states it, middlebrow Sunday supplement stuff.

One very obvious point, which has been made several times by others, is to ask why he thought his ‘theory of omission’ was so ‘new’ or even revolutionary when for many years writers had been composing their work specifically to allow and encourage their readers to ‘read between the lines’. We, the readers, read between the lines, for example, in Hemingway’s story Hills Like White Elephants and gather a guy is trying to persuade his gal to have an abortion. But ‘writing between the lines’ (if you see what I mean), is also something writers of fiction had been doing long before that story was written.

A Hemingway freak might counter that ‘that isn’t what Hemingway meant’ by his ‘theory of omission’, to which I would counter-counter that if Hemingway did mean what he seems to have meant — that ‘you could omit anything . . . and the omitted part would strengthen the story’ — he was kidding no one but himself if he meant that he could leave out a detail completely and I mean completely (like the suicide in the oft-given example of his story Out Of Season), but that the reader would somehow still ‘pick up’ on that detail. It’s all just a tad too pseudo-metaphysical for me. Or perhaps I have got it wrong and he doesn’t quite mean that, either.

Certainly, many of his stories were not ‘about’ what they were ostensibly ‘about’, but that has been the essence of interesting and engaging fiction for many years before young Ernie first put pen to paper. Why did he think he had hit upon something new?

On the question of ‘Hemingway’s modernism’, it is also worth mentioning that he was notoriously, not to say very ostentatiously, anti-intellectual. There are suggestions that, much like his very ostentatious and increasingly unconvincing displays of machismo, the anti-intellectualism was something of a front.

One friend from on the Toronto Star, Greg Clark, who had known him when he first turned up in Toronto in 1919, remarked when he returned to the paper in 1923 for a staff job after freelancing in Paris (for what turned out to just a few months): ‘A more weird combination of quivering sensitiveness and preoccupation with violence never walked this earth’. But whatever the reason for it, Hemingway was remarkably reluctant to discuss intellectual matters.

His friend in Paris (and later until, invariably and inevitably, Hemingway fell out with him) Archibald McLeish remembered many occasions when he attempted to start a discussion and tease out Hemingway’s thoughts on aesthetics and related matters, only for the great man swiftly to change the subject to hunting or fishing or boxing or bullfighting or some such topic.

For me the task is now to learn a lot more about ‘modernism’. But at least I now realise I know next to bugger all, so that’s a start of sorts.

Pip, pip.

Here’s a bit of modernism for you to keep you happy . . .

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)